The 'Mona Lisa of ceramics' sat behind glass for 115 years. We digitized it so people could finally touch it.

The 'Mona Lisa of ceramics' sat behind glass for 115 years. We digitized it so people could finally touch it.

Adelaide Robineau was a pioneer. She was one of the first people on the planet to figure out a recipe for porcelain that allowed for hand work. This was groundbreaking—porcelain had been an industrial secret, controlled and guarded.

And what did she do with this discovery? She shared her recipe for free.

She started journals. She started writing so that other women could do what she had done. She was experiencing extreme adversity during her time due to her gender—women at that time were only allowed to paint on top of other people's porcelain. They weren't allowed to throw their own pieces or craft their own vases.

Adelaide Robineau did it all. She created her own sculptures. She fired them herself. She shared her knowledge freely.

Adelaide Robineau broke barriers and shared knowledge. 115 years later, we're helping her masterpiece break through glass and reach more hands.

Failure: Huge chunks of data missing. Pixelated. Blurry. Some scarabs gone entirely.

What we expected: Clean, complete, high-resolution data

Twelve hours on site plus several months of processing equals an expensive failure. But without that failure, we never would have asked the right questions.

Scanning in the dark revealed what scanning in the light had hidden.

We thought once we had clean data, printing would be straightforward.

We were wrong again.

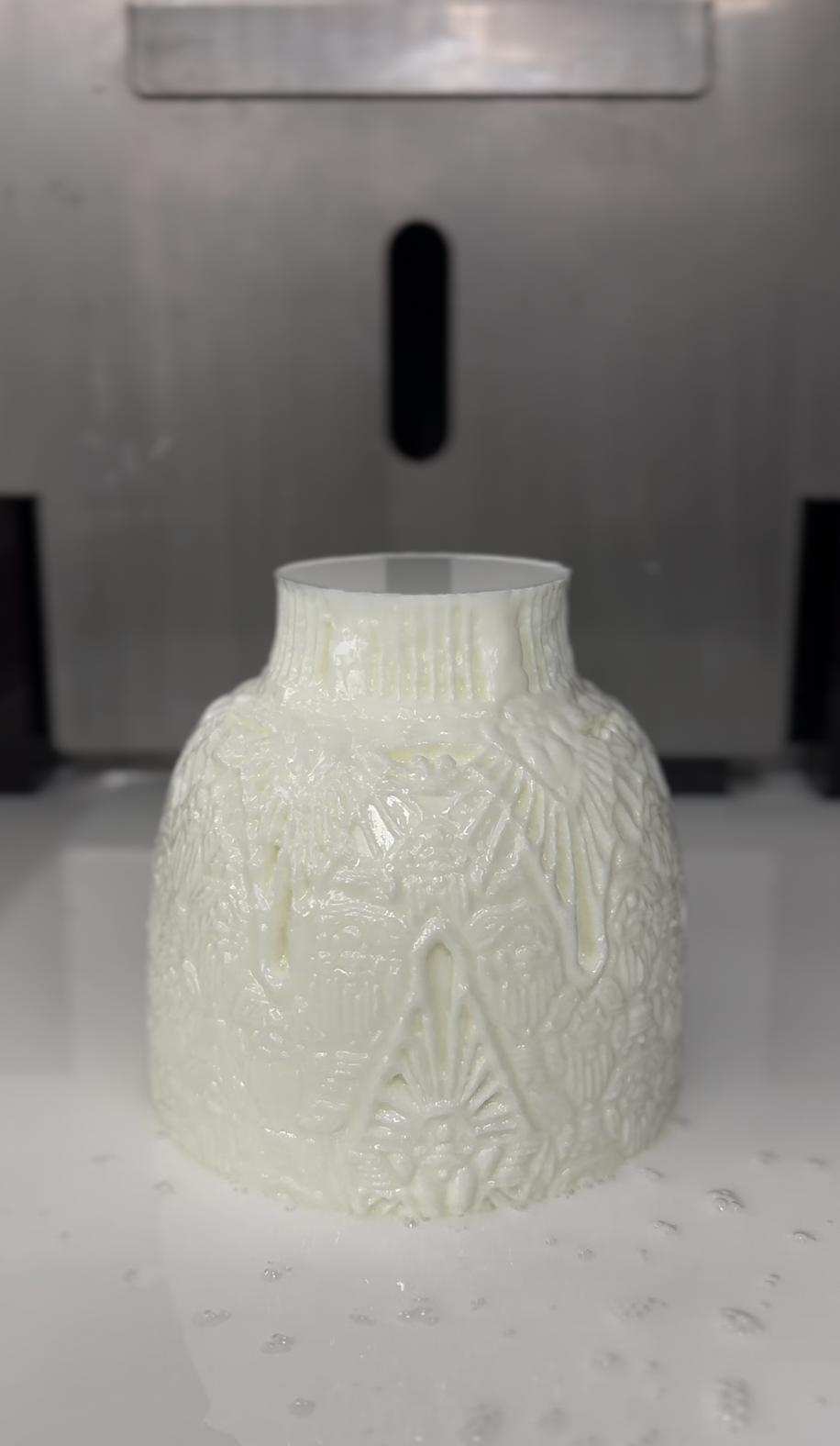

Given the Scarab Vase's scale and immense detail—thousands of individually carved scarabs, each with intricate relief work—it required the advanced capabilities of Think Variant to realize this magnificent piece.

Think Variant had to develop new techniques in SLA (stereolithography) resin 3D printing to achieve the level of detail Adelaide had carved by hand 115 years ago.

This wasn't just replication. This was translation—from atoms to ones and zeros and back to atoms again, with fidelity that honored Adelaide's original craft.

When atoms become ones and zeros, new relationships become possible.

| Title | Adelaide Robineau Scarab Vase Digitization |

|---|---|

| Original Artist | Adelaide Robineau (1910) |

| Year | 2024-2025 |

| Client | Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse NY |

| Category | Cultural Heritage Preservation, Accessibility Innovation |

| Technology | Photogrammetry, infrared 3D scanning, SLA 3D printing |

| Fabrication Partner | Think Variant (advanced SLA techniques) |

| Challenge | Porcelain's unique light absorption/reflection properties |

| Failed Attempt | 12 hours scanning in ambient light → pixelated, incomplete data |

| Solution | Scanning in complete darkness with controlled lighting |

| Result | "Please Touch" version installed September 2025 |

| Impact | First tactile access to 'Mona Lisa of ceramics' in 115-year history |

| Philosophy | When atoms become ones and zeros, new relationships become possible |

Now that we've made one masterpiece touchable, what other untouchable works can we bring within reach?